But what does it all mean? (Don’t Answer That.)

Arthur C. Clarke, the co-writer of 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY, once said, "If you understand 2001 completely, we failed. We wanted to raise far more questions than we answered.”

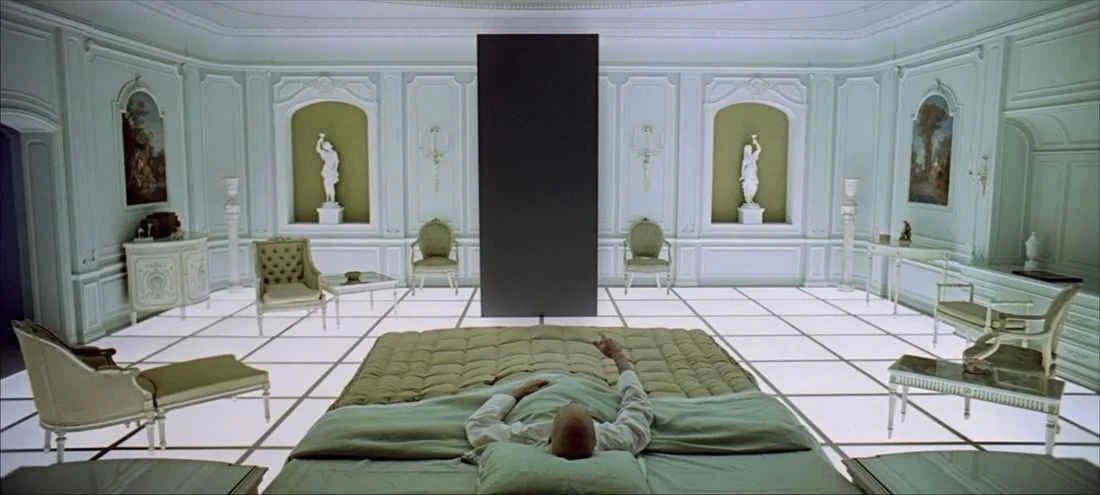

That has to be a relief to viewers of a film so heady, epic, and mind-boggling in scope. I know that third act always fries my brain; I feel for Dave Bowman while he’s tripping through the different dimensions. The movie is a three-hour marathon, and the finish line doesn’t offer the relief of a simple ending. And this is a good thing.

Let’s face it: art is inherently subjective, and viewers aren’t going to take away the same emotional experiences and interpretations from any given film. We may be nudged in a certain direction, perhaps plot- or mood-wise, but the filmmaker can only guide our viewing experience to a certain extent; personal attitudes and opinions will color our individual perceptions of it.

An effective film (not just SciFi, but any genre) challenges the audience by leaving room for interpretation, embracing the idea that audience insights will vary. Hooray for open endings, that’s what I say. The filmmaker creates a world, immerses you in said world, and allows you to find meaning within it. Sometimes the ambiguity does not manifest until the ending, as in Christopher Nolan’s INCEPTION. Relatively straightforward, the film holds our hand through various plot twists and complications. It’s not until the very last shot (the spinning top seen ’round the world) that we’re forced to question everything we just saw. Did the plan ever come to fruition? Was it all a dream? If so, when did the dream start? It demands a second viewing (and third, fourth…) to pick up details we may have missed, and perhaps these later viewings will change our takeaway significantly.

Other times, the uncertainty will linger throughout the film. As many times as I’ve seen Richard Kelly’s DONNIE DARKO, I’m still stumped whenever anyone asks me what it’s about. But it’s not that I haven’t taken anything from it, rather the sheer number of ideas it presents. Kelly’s world is a very purposefully crafted one, though it’s not always clear just what is happening within it. Is Donnie a superhero for the angsty, suburban generation who ultimately sacrifices himself for the greater good? Is he a time traveler? Is he a victim of the dawning era of prescription drugs, suffering hallucinations? All? None? It’s a weird movie, but not in a Lynchian, weird-for-the-sake-of-weirdness way. Kelly has obviously very carefully built the world and the story, but the overarching theme of time travel is overwhelming and ultimately brings up more questions than answers.

Ridley Scott’s BLADE RUNNER is an interesting example in that different ambiguity unfolds within different versions, particularly in the ending. In the original theatrical version, cop Deckard and replicant Rachael ride off into the sunset, Deckard loving Rachael in spite of her otherness. In the director’s cut, however, a dream sequence added earlier in the film complicates the ending and suggests that Deckard himself could be a replicant. Is he? If so, is the department knowingly sending him out to kill his own kind? How can you know if your memories are real? It’s interesting that, through slightly tweaked versions of the same story, Scott is able to plant different questions in our brains.

Film as an art medium has myriad materials and tools at its disposal: lighting, music, camerawork, etc. With so many variables--and add to that individual insight--it’s no wonder that each viewer will come up with something a bit different than the person next to them by the time the film has finished. The draw of films, especially those with open endings, is this: in place of passive viewing, there can be participation through perception. Struggle with the loose ends; entertain alternate ideas. As our friend Donnie said, “I can only hope that the answers will come to me in my sleep.” Or, you know, repeated viewings, online discussions, and arguments with friends. It’s the conversation, not the conclusion, that counts.